Turkey is a country with obvious symbols: the state flag which marks the “modern totem”, photos of the eternal Ataturk (founder of the republic), exotic mosques, and symbols that emphasize national(ism) spirit. The romanticism towards this symbol also simultaneously captures the awareness of the Turkish people themselves, who inevitably have given birth to fanaticism in the realm of nationalism, secularism, religion, and other ideologies. In fact, extreme and excessive attitudes (aşırı) towards various symbols that hardening identity are clearly found throughout Turkey.

One of the newest and contested symbol is the revocation of the identity of the museum for Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. The decision of the Turkish high court to return Hagia Sophia status to mosque has been decided, and this legal step means that it also revokes the previous decision number 2/1589, 11/24/1934 in 1934. The decision to restore the mosque identity for Hagia Sophia is very interesting to look at, which, for me, is part of the Erdoganism inauguration (symbolism).

Erdoganism

The term Erdoganism is actually quite familiar in political studies. Erdoganism emerged in mid-2014 especially after the first direct presidential election event in the history of the Turkish Republic, on August 10, 2014. The presidential election at that time, as reported by Sabah Daily, was won by Erdogan by winning a majority of votes by 51.79%, defeating two rivals namely Ekmeleddin Ihsanoğlu from the secular group and Selahattin Demirtaş from the Kurdish community.

Since that year, titles that have confirmed Erdogan such as tek adam (the only man) and reis (leader) who emphasized the strength of his position on the national stage have emerged. The mention of tek adam dodged the blinds with the dictator’s accusation, as reported in Sputnik News.

In his column in the daily Cumhuriyet entitled Erdoğanizm Türkiyesi (The Erdoganism of Turkey, July 10, 2018), Ahmet İnsel acknowledged that the term Erdoganism could not be ascertained when it was first used, but the designation was used after the presidential election on August 10, 2014. By filtering out perceptions from the mass waves, İnsel mentioned that the understanding that developed behind the wave of Erdoganism was similar in support of Erdogan’s president with the values he had championed such as dindar (religious), muhafazakâr (conservative), milliyetçi (nationalist) and sadık (loyal).

As a journalist, İnsel carefully observes the concepts that have been built behind Erdoğanism and discovers three principles, namely muhafazakâr, milliyetçi and dinî kimliği (religious identity).

While on the international stage, the Erdogan phenomenon has been raised as a special topic with various designations and perspectives: Time magazine released a special report titled Erdogan’s Way (28 November 2011), The Economist with the title Erdogan’s New Sultanate (6 February 2016) and other international media . Their presence in the discourse of the study of figures – with experts and researchers who play a large role in it – is able to explore important aspects that have been the key to the Erdogan movement which has controlled Turkey since 2003.

Erdogan has perfectly become Turkey’s strongest figure after Ataturk with a variety of narratives that have developed internally in Turkey and on the international stage. An open statement from former 12th NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen at the symposium at Hasan Kalyoncu University, Gaziantep, 19-20 December 2014, that Erdoğan, Atatürk’ten sonraki en güçlü lider (Erdogan was the most powerful leader after Ataturk) had added the legitimacy of Erdogan’s figure in the international public (Sujibto, 2019).

Ataturk vs Erdogan

These days, if we look at the rooms in many Turkish government offices before and after Erdogan became president, something has changed and is actually quite obvious: the addition of a self-portrait of Recep Tayyip Erdogan. I do not know for sure when the picture frame with Erdogan’s photo began to be placed parallel to the photo of Ataturk and whether there are rules for what offices may / may not install it.

To be sure, after the Turkish state system officially changed from parliamentary to presidential in 2017 and then confirmed Erdogan to become an executive president in the 2018 elections, Erdogan’s photos have begun to be easily found in Turkish government offices.

Symbols of two figures who have different ideologies but who share the same extreme power for Turkey. Both of these big names have been very difficult to be erased from the wilderness of politics and memory of the Turkish people going forward. Ataturk continues to ignite as the Republican Father who is also a hero to the people of Turkey, while Erdogan will continue to grow as a great figure who is able to develop a more advanced and respected Turkey.

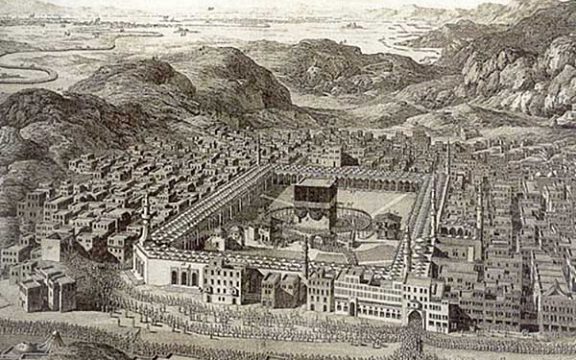

Being a museum in 1934, the Hagia Sophia (museum) is a product of secular politics which many refer to as a symbol for the process of secularization of Turkey. At that time, the strong figure who oversaw Turkey’s modernization and westernization process was Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, where in addition to turning Hagia Sophia into a museum, the Republican father also froze some madrasa education in several regions in Turkey.

At that time, in the memories and memories of the right-leaning Turkish people and those who specifically rejected secularism, there was a systemic effort to “distance” Turkish society from Islam and all identities that smelled of Arabic in particular. At that time, the Anatolian identities were explored as clearly as possible and at the same time were massively introduced into the community.

At that time, the face of Turkey “facing” to the West.

The inauguration of the Hagia Sophia mosque on July 10, 2020 is a product of Islamist politics which is considered by many to be the revival of Islam. If agreed with the view that the destruction of Hagia Sophia is an affirmation of the identity of the secularization process, the return to the mosque is a visible contestation of the Islamists. The strong character behind this decision, while remaining through legal channels, is Erdogan. In the future, especially for the younger generation of Turkish successors, the decision on Hagia Sophia will continue to reflect the name of one character, Erdogan, as well as the Hagia Sophia museum which for years reflected the great name of Ataturk.

In short, if Ataturk succeeded in making the Hagia Sophia a museum, Erdogan had also succeeded in turning it back into a mosque. If we put this symbolism face to face, secularism and Islam have paid off. But is the decision finished here? Of course not. Extremely large fees to be paid by the government and people of Turkey, from the political, economic, and humanitarian aspects of religious relations (Islam-Christian).

Besides the aspects of symbols and patrons, of course there are many perspectives that can be used to analyze the Hagia Sophia. Debate and discussion about it openly continued both in Turkey and internationally which emphasized how urgent the site was seized by Sultan Fatih in 1453.

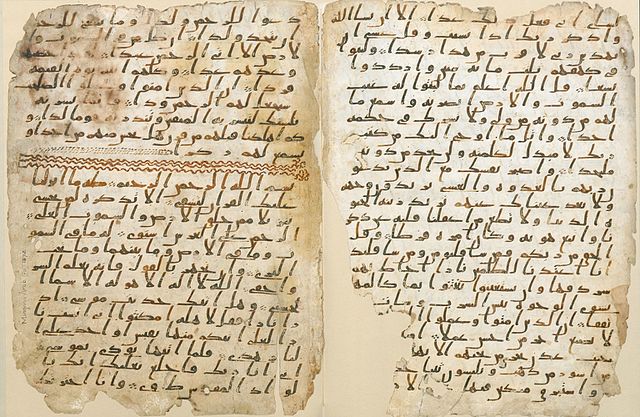

Finally, I review with certainty that Erdoganism is becoming stronger with political endeavors in the form of decisions against Hagia Sophia. As a great magnet for two religions, the former orthodox cathedral named Latin Sancta, built in 537 under Justinian’s rule, can be read as a dynamic symbol contestation and also determines the direction of Turkish politics going forward, both with Erdogan.

![Islami[dot]co](https://en.islami.co/wp-content/themes/jambualas/images/logo.png)