There is a missing ingredient in media descriptions of Indonesia’s new president, Abdurrahman Wahid, familiarly called Gus Dur. We know that he is a Muslim cleric, the head since 1984 of Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), Indonesia’s and perhaps the world’s largest organization of traditional Muslim religious scholars and teachers. His near-blindness and physical frailness, the result of diabetes and two recent strokes, were painfully apparent to television viewers world-wide who watched the sessions of the People’s Consultative Assembly when he was elected and sworn in as Indonesia’s fourth president.

As a political tactician, he is reported to be both adept and mercurial. Adept, in the way he carved out and defended his position as the leading protagonist of democracy in the most repressive days of the Suharto government. Mercurial, even erratic, for his emotional outbursts, his tendency to believe the most outrageous conspiracy theories, and his strategic zigzags that have occasionally comforted his enemies and confounded his friends.

We are also beginning to understand that this is a most unusual Muslim cleric. He is a religious pluralist who believes that religion is a matter of personal choice, and has consistently acted on that belief for decades. During the Suharto years he publicly defended the rights of non-Muslim minorities as well as Muslim organizations considered heretical by his co-religionists and by the state. He is a European-style social democrat committed both to representative democracy and to the use of state policy to reduce inequalities of opportunity and of condition. Perhaps most surprising to secularized Indonesians, he has been an active member of the modern Jakarta intellectual elite, engaging the issues of the day through his writings and organizational activities. For several years in the 1980s he scandalized more conservative Muslims by serving as a juror at the national film festival, the equivalent of Hollywood’s Academy Awards.

What is missing from this picture is a deeper understanding of the kind of leadership Gus Dur, health permitting, will give his country. I first met him in the mid1970s, shortly after his return from study in the Middle East, when he was just beginning to establish himself in the group of Jakarta political intellectuals centered around Tempo, then as now Indonesia’s leading weekly newsmagazine, and LP3ES (Institute for Economic and Social Research, Education, and Information), an applied social science research institution staffed by bright young urban Western-educated socialists and modernist Muslims.

Gus Dur was not exactly a stranger to Jakarta life. His father was an NU leader and independent Indonesia’s first minister of religion, and the family had lived in the capital for some time. But his years as a student in rural Islamic boarding schools, his higher education in Baghdad and Cairo, and his NU affiliation made him suspect in the eyes of Jakarta intellectuals. To both the secular socialists and the modernist Muslims, he represented the backwardness of a village Islam still chained to the teachings of medieval jurists and mired in the irrationality of both sufi and indigenous Indonesian mystical beliefs and practices. In the 1950s, the time of Indonesia’s first democratic experiment, national-level NU politicians—including Gus Dur’s father—were mocked as hayseeds and either isolated from national office or confined to the ministry of religion.

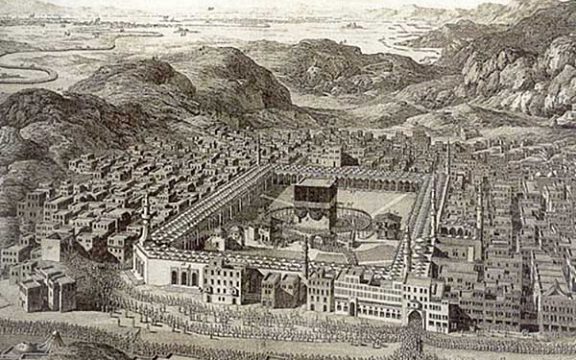

As a young boy, Gus Dur directly observed the mistreatment of his NU elders, and shared their resentment. Many years later, in interviews with me and others, he often complained about the continuing arrogance of NU’s enemies, especially the Muslim modernists. NU had been founded in 1926 by traditional rural-based Muslim teachers and scholars concerned to stem the advances made by the urban, more Western-educated modernists, who preached direct interpretation of the Qur’an by contemporary believers. NU’s teachers and scholars wanted to preserve the classical Sunni tradition of interpretation within jurisprudential schools, which for centuries had formed the basis of Islamic education in Indonesia. For a brief period in the late 1940s and early 1950s the modernists and traditionalists joined forces in a single political party, but in 1953 NU leaders split to form their own party. Since that time the two camps have remained separate and hostile, though forces for rapprochement have also been at work, especially in recent years.

Gus Dur’s understanding of leadership is rooted in his NU background. In a casual conversation some years ago, I asked him what he liked to read. He answered that his favorite contemporary novel was Chaim Potok’s My Name is Asher Lev. When I asked him why, he replied simply that it was a mirror.

The eponymous hero of My Name is Asher Lev is a young observant Jew growing up in Brooklyn in the 1940s and 1950s. His family life is steeped in religious tradition. Both of his parents are the descendants of several generations of rabbis and scholars. His father travels throughout the country and Europe helping to rescue Jews behind the Iron Curtain and establishing yeshivas “at the request of the Rebbe” who is the leader of their Hasidic sect. His father’s great-great grandfather, who appears to Asher in disturbing dreams as his “mythic ancestor,” transformed a despotic Russian nobleman’s estates into a source of immense wealth. He then spent the rest of his life travelling “to do good deeds and bring the Master of the Universe into the world,” that is, to restore the balance he had upset by enabling the nobleman to brutalize his serfs. Asher’s grandfather, for whom he is named, travelled throughout the Soviet Union as an emissary of the father of the present Rebbe. He was murdered by a drunken peasant while on his way home from the Rebbe’s synagogue on the night before Easter. Asher’s mother, the descendant of “one of the saintliest of Hasidic leaders,” is devastated at the beginning of the novel by the accidental death of her only brother, but recovers by dedicating her life to completing his work for the sect.

From an early age Asher understands that he has a unique gift. He is an artist destined for greatness. The demands of art—portrayed by Potok as an autonomous world of meaning with its own values and standards—soon cause conflict with his parents, particularly his father, for whom becoming an artist is foolishness, “not for Torah,” perhaps even temptation from the sitra achra, the Other Side. The wise Rebbe, with a broader vision than Asher’s father, intervenes, introducing Asher to Jacob Kahn, a great artist who revolutionized sculpture as Picasso revolutionized painting. The Rebbe says, “I pray to the Master of the Universe that the world will one day also hear of you as a Jew…. Jacob Kahn will make of you an artist. But only you will make of yourself a Jew.” Kahn becomes his teacher and patron, eventually arranging a series of one-man shows at which he is acclaimed by the critics as a major new artist.

The conflict with his parents, however, intensifies. He is driven by the need to express his anguish and torment in his art. “For the unspeakable mystery that brings good fathers and sons into the world and lets a mother watch them tear at each other’s throats.” He paints a metaphoric crucifixion scene (he chooses Christian symbolism because Judaism, he says, offers nothing comparable), his mother with her arms extended above the window of the family living room, her face split into two segments, his father and he standing below with an attache case and a palette respectively, demanding the impossible, that she choose between them.

His parents are deeply shocked by the painting. Even the Rebbe abandons him this time. “’Asher Lev,’” the Rebbe said softly. ‘You have crossed a boundary. I cannot help you. You are alone now. I give you my blessings.” At the end of the novel he leaves Brooklyn for Paris, but he is still “Asher Lev, Hasid. Asher Lev, painter.” He hears his mythic ancestor: “Come with me, my precious Asher. You and I will walk together now through the centuries, each of us for our separate deeds that unbalanced the world.” He will be a great painter, but in doing so he will also continue to hurt the people he loves. There is no way out of the dilemma.

What is the connection between My Name is Asher Lev and Abdurrahman Wahid? At the simplest level, his appreciation for the world of Asher Lev reflects his empathic ability to enter the consciousness of others, remarkable in his case since there is little love for Jews among most Indonesian Muslims. He read in the novel the Hebrew greeting and response “Sholom aleichim, aleichim sholom” and saw, he told me, the familiar Arabic “Salam alaikum, alaikum salam,” used by Indonesian Muslims as a mark of their Islamic identity, differentiating them from others. To Gus Dur, however, the similarity of the phrases signified not only the common origins of the two religions but more deeply the universality of the human religious experience. His love for the novel also helps to explain his long fascination with Jews and Israel, a country that he has visited several times as a private citizen and with which he now proposes as president to establish economic relations.

More deeply, however, the novel is a mirror to Gus Dur for two reasons. First, the Hasidic yeshiva-centered world described by Potok looks remarkably like the pesantren or Islamic boarding school-centered world of traditional Indonesian Islam. To be a student in these schools is to be a member of a moral community possessing shared values and beliefs that differentiate initiates from outsiders. It is an intense experience that creates strong lifelong bonds among the students and between them and their teachers. At the center of both is a respected, even charismatic, leader, the Rebbe or the Kiai, who is to be obeyed without question. The yeshiva and the pesantren are also central institutions of the communities they serve, Hasidic Jews and traditional Indonesian Muslims. The Rebbe and the Kiai are consulted as a matter of course when serious family or community problems arise, and their advice is rarely rejected.

Second, as strong, even charismatic, leaders the Rebbe and the Kiai have the principal responsibility for shaping their communities’ futures. In order to respond to the challenges of their time and place, they must have a broader social and cultural horizon than their members. They must be bridges to other worlds, non-observant Jewish and Gentile America in the case of the Hasidic yeshiva, modern Indonesian and global society and culture in the case of the Muslim pesantren. In this respect the Rebbe in My Name is Asher Lev affirmed for Gus Dur his own conception of the ideal NU Kiai, a leader who is firmly rooted in the tradition of classical Sunni Islam and for that very reason is capable of flexibly interpreting or even reshaping that tradition to meet the challenges of the modern world. It is the Rebbe, not Asher’s equally pious but intellectually and morally conventional father, who believes that it is possible to be both an observant Jew and a great twentieth-century artist. By giving him Jacob Kahn as a teacher (in itself a gesture natural to the yeshiva tradition), the Rebbe makes Asher’s success outside the Jewish world possible.

For Gus Dur there is a very personal element in all this. In some respects, he is both the Rebbe and Asher Lev. His grandfather was the founder of NU, his father a prominent NU leader, and it was expected that Gus Dur would eventually step into their shoes. As a boy and young man, however, he was a maverick with a sharp mind, uncomfortable with conventional Islamic beliefs and practices and eager to expand his horizons.

After his study in Baghdad and Cairo (where he earned no degrees) he spent time at several European universities before returning home in the mid-1970s. He then began his career as a Jakarta-based social activist, which included writing over the next several years a series of remarkable columns in Tempo magazine. Each of these columns told a story about a wise Rebbe-like Kiai who solves a contemporary social problem that conventional approaches, based on modern technology or organization alone, could not overcome.

In these columns it is easy to see the Gus Dur who has always had a chip on his shoulder, who disdains the modernist Muslims too eager to discard Islamic and Indonesian history and culture in favor of an unmediated application of the Qur’an to contemporary life. But his larger purpose was a positive one, and not restricted to the Muslim community: to demonstrate that traditional roles, values and practices like those of the Kiai are both necessary to the transition to a modern society and an inescapable part of the specifically Indonesian modernity that he hoped to build. He was also implicitly offering himself, though for many years without much hope of success, as a kind of Kiai-President, a blend of traditional and modern roles.

The concept of a Kiai-President has its strengths and weaknesses. Perhaps its greatest strength is its familiarity and therefore instant legitimacy to tens of millions of Indonesians from most regions and ethnic backgrounds. This characteristic will certainly help the reformers, Gus Dur among them, who are attempting to replace former President Suharto’s army-backed authoritarian New Order with a more democratic system. Its most glaring weakness is its lack of rules and procedures through which leaders can be held accountable to their constituencies. The Kiai achieves his position through a combination of birth, education, and a gradual acceptance of his knowledge and teaching ability by other Kiai, potential students and their parents, and the larger traditional Muslim community. There is no regular procedure by which he is chosen or, perhaps more importantly, by which he can be removed.

For the most part, therefore, the institutions which hold the president accountable will have to be borrowed from other traditions, notably that of the West and democratic East Asia. This process was begun by President B. J. Habibie, the successor to Suharto, whose government quickly bowed to popular pressure for a free press and democratic elections. It is continuing under Gus Dur, the first democratically elected president in Indonesian history. The People’s Consultative Assembly that elected him is now preparing constitutional amendments and regulations that will constrain future presidents and insure a greater role for Parliament and an independent judiciary. The new president has also responded quickly to regional demands to create a de facto federal system, in which provinces will elect their own legislatures and governors.

Despite its lack of a concept of institutional accountability, traditional Islam may yet make a significant contribution to Indonesian democratization through Gus Dur the Kiai-President. Both the Rebbe in My Name is Asher Lev and the many Kiai whose stories were written down by Gus Dur were distinguished for their combination of deep roots and an open, flexible, and inclusive approach to outsiders and to the future.

In the end, Asher Lev went too far, crossed a boundary where the Rebbe could not go, leaving Asher with only his mythic ancestor to accompany him. On his past record, there is a good chance that Gus Dur will draw the boundaries in a way that will keep the major players—ethnic and regional as well as religious—inside the nation while moving steadily toward democratization of the state.

*William Liddle, Professor of Political Science, The Ohio State University.

![Islami[dot]co](https://en.islami.co/wp-content/themes/jambualas/images/logo.png)